Let's Talk about the Elephant

Making sense of the reinforcing dynamics driving our negative spiral

Welcome back! So glad you are continuing on this journey with me, and grateful to everyone for the enthusiastic response to the launch of this conversation. Where my first two posts offered an introduction and an executive summary, I’ll now start to share what I learned in more depth.

Over the coming posts, I’ll walk through each of the five reinforcing domains that emerged as central to the opportunities and challenges before us. This is what I refer to as The Elephant. It’s what we see when we look at the whole picture of what’s happening in our world today, and not just the parts that are visible from where we sit. I originally put this analysis together in the summer/fall 2024, so it doesn’t attempt to address the more recent evolution of our political landscape.

This post will focus on setting the stage and then introduce the first major domain, Capitalism and the Economy. Where I originally thought that all the domains were equally culpable for our current spiral, I’ve since concluded that the nature of how capitalism is implemented today, without guardrails to safeguard people and the planet, is the fundamental driver of our dysfunction. All of which is to say, this post is at the heart of why I believe we are where we are.

Note: Each section starts with quotes that help frame the breadth of perspectives that I encountered. These are primarily drawn from public sources and are intended to be illustrative. They are not from the interviews themselves.

The Elephant

Technology is the glory of human ambition and achievement, the spearhead of progress, and the realization of our potential. We believe that there is no material problem – whether created by nature or by technology – that cannot be solved with more technology.

- Marc Andreesen, The Techno-Optimist Manifesto, October 2023

We’re on the edge of an abyss. We face the greatest cascade of crises in our lifetime.

- Secretary General Antonio Guterres, United Nations General Assembly, September 2022

It is the best of times. It is the worst of times. Quality of life is better for millions of people around the globe, artificial intelligence is poised to make life-changing discoveries in science and medicine, and yet we are more divided, more fearful, and more uncertain about the future than ever before. We are simultaneously anticipating breathtaking breakthroughs and contemplating our own extinction.

This moment is a wake-up call to address the systemic nature of the challenges we face. Growing wealth inequality, threats to democratic institutions, climate instability and the explosion of generative artificial intelligence are driving fear and insecurity among individuals and families around the world. These feelings feed rising distrust in institutions and “other” people and are fed and exacerbated by targeted media channels, social media algorithms, and our human tendency toward recency and confirmation biases.

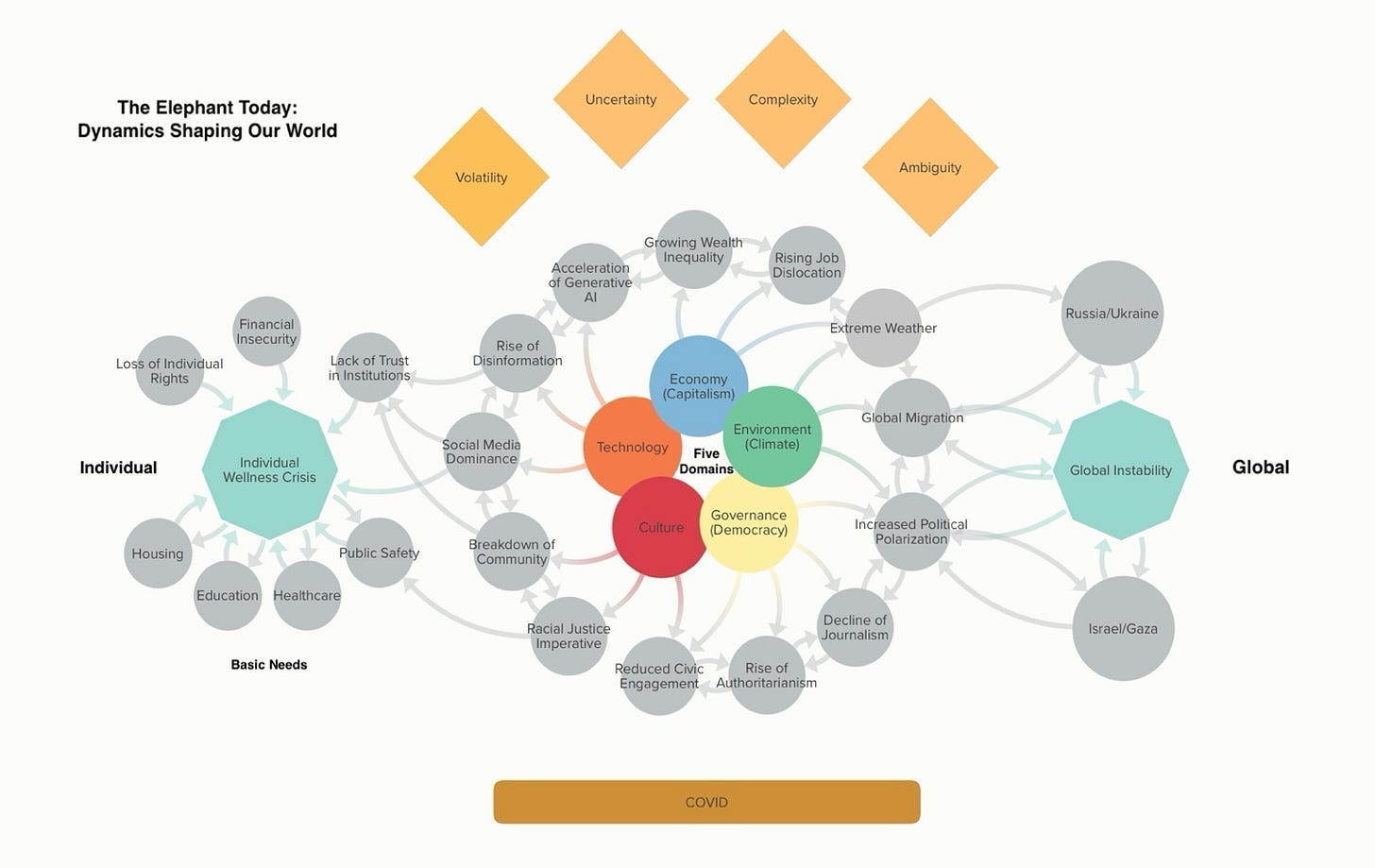

The state of the world has become volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA). This acronym was originally developed by the military to address a more complex multilateral world at the end of the Cold War, especially post 9/11, and was subsequently adopted in business and to some extent education. It was intended to apply to discrete situations where these dynamics made the future unpredictable, failure was to be expected, and learning became critical. Now it is difficult to find a niche where it does not apply.

If not managed well, VUCA can translate into organizational dysfunction, poison culture, and drive individual insecurity. One cannot help but see the parallels in our country and the world. It requires us to admit the “old ways” of working no longer apply. We need to be open to new means of operating that match the moment.

To do so, we first need to understand what is happening. While complex, my illustration above is an attempt to summarize the dynamics at play. If you want a closer look, you can click on the image. In it, five core domains – economy, environment, governance, technology, and culture – create a complex, mutually reinforcing system which can move in positive or negative directions depending on the moment in history. In recent history, the dominant momentum is negative.

Surrounding the five depicted domains are resulting dynamics, such as climate instability, political polarization, job insecurity driven by AI, the breakdown of community, and the rise of authoritarian leaders, each of which also have reinforcing impacts on each other.

To the left are the impacts on individuals, families, and the systems upon which they rely, such as healthcare, education, public safety, and human rights.

To the right are geopolitical dynamics which can – and are – further destabilizing society. Underlying everything is a recognition that COVID exacerbated the inequities in our society and turned misinformation and our post-truth reality into a life-or-death situation.

And taken together, all of these elements create a self-reinforcing dynamic like grinding gears that further tighten to exacerbate volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity.

Happily, it does not have to be this way, and I promise we will get to positive trends and reasons for optimism. The next chapters are dedicated to looking at the core domains as they are today, highlighting collective insights and, where salient, my personal observations. Rather than trying to be comprehensive, I sought to focus on the frames I found most useful to explain how we reached this point and the nuances and facts that emerged from so many varied perspectives. The first of these is the critical role of extractive capitalism in driving so many of the issues we face.

Capitalism and the Economy

People are the creators of prosperity. More people – in an environment of freedom and free markets – means more prosperity.

- Steve Forbes, Editor-in-Chief, Forbes magazine

Capitalism does not permit an even flow of economic resources. With this system, a small privileged few are rich beyond conscience, and almost all others are doomed to be poor at some level. That's the way the system works. And since we know that the system will not change the rules, we are going to have to change the system.

- Martin Luther King, Jr.

Markets are powerful forces for innovation and growth, and capitalism can be a positive force for good under the right circumstances. However, pursuing short-term financial gain without guardrails and unlimited growth with GDP as the sole indicator of societal wellbeing is clearly no longer working for people or the planet, despite having gained momentum for a period of time in the last century. In researching this question, I sought to understand why the middle class flourished in the United States in the latter half of the last century and then was so quickly broken down, as compared to the time prior and since, when society reverted to more of a bar bell structure.

One potential explanation that resonated for me is that widespread fear of communism in the decades following World War II drove a willingness among political and business elites to prioritize opportunities for working class Americans – primarily white – to secure a good life for themselves and their children, ensuring that communism had limited appeal by comparison. For the first time, US income became broadly distributed across a bell curve with a robust middle class. They believed we had unlimited planetary resources and for the dominant culture, the system worked. This was also a potent political tool, which Richard Nixon famously used to his advantage in the 1959 Kitchen Debate with Nikita Khruschev. The middle class in turn was a powerful engine for the economy and drove economic growth. For a time, the planet could absorb the cost.

As Keynesian economics (government spending into economic downturns) gave way to Reaganomics in the 1980s and then full-blown Neoliberalism (tax cuts and market self-regulation) in the 2000s, the world concurrently saw the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War. Without the fear of communism to offset financial incentives, there was no longer a compelling reason to hit the brakes and make sure quality of life persisted for everyone.

As a result, we have seen a great hollowing out of the middle class and a dramatic rise in wealth inequality, such that today the wealthiest 10 percent of people in the US have 75 percent of the wealth, the 20 richest billionaires have more wealth than bottom 50 percent of Americans, the eight richest people globally have more money than half the world’s population,[1] and a 2024 Oxfam report shows the wealthiest one percent increased their fortunes by $42 trillion over the last decade.[2]

Many commented on this staggering and growing wealth inequity as one of the most noteworthy trends and biggest challenges we face. I will take it a step further to say that this focus on financial growth at all costs together with the extractive nature of our economy is the central issue driving our dysfunction. Competition and free markets are still the most efficient way to support innovation and create value, but it needs to be with the explicit goal of serving people and the planet, not at their expense.

In particular, academic and philanthropic executive Larry Kramer points to the broadly (but not yet universally) acknowledged failure of neoliberal economics and the absence of a common rational and predictable framework alternative around which to organize society. The resulting vacuum creates fear and uncertainty, and with no agreed upon “right” way to organize society, allows for manipulation and false theories to be promoted by self-interested actors. There is a clear need to rethink the relationship of markets and governments relative to society, and do so within the ecological limits of the planet.

In short, we need a new economic paradigm. Personally, I am encouraged by economic models like Kate Raworth’s “doughnut economics,” tools like the Social Progress Index, and the collaborative work of the Wellbeing Economy Alliance to support emerging movements and models that illustrate that such a shift is not only possible but is actually taking root in cities and countries around the world. These efforts recognize the value of free markets as long as they are implemented with adequate social safety nets for individual survival and keep human activities within the bounds of what the planet can support.

A major challenge to making this shift and a key attribute of our VUCA world is the accelerating rate of change in our society and the world, which is exponential now, driven by decades of deregulation and regulatory capture, and exacerbated by rising climate instability and the advancement of technology without adequate guardrails. This shift leaves no time to understand the implications of one set of changes before the next change is layered on top. To make matters worse, most people now believe that free markets and limited regulation are good for the economy, so there is no broad consensus on a need to shift.

The result is what philanthropy and corporate executive Kriss Deigelmeier refers to as “capitalism at speed” with a singular focus on shareholders and quarterly returns. Business models and norms have never evolved so quickly, and while we know the implications are significant for people and the planet, with many being potentially positive, it is not yet clear who if anyone will be empowered to anticipate and mitigate the negative. If we have learned nothing else over the last 20 years, or indeed over the last 150 years of industrialization in America, we know that corporations cannot be counted upon to regulate themselves for the benefit of society.

Over the last three years, the government attempted to counteract some of these economic effects and rebuild coming out of COVID with a return to Keynesian economics and massive trillion dollar investments through the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the Inflation Reduction Act, including massive tax credit incentives for businesses to hire and grow. These investments have the potential to create unprecedented jobs and economic boom if they are allowed to proceed and people can be skill-matched. However, it’s unlikely that such efforts will continue under the current US administration.

While spending into a downturn has proven effective in the past, such as with The New Deal in the 1930s, spending at this level, first with COVID relief and then with the legislation above, has also contributed significantly to the ever-growing US national debt, which is now $36 trillion or 123 percent of GDP, significantly exceeding the 70 percent ideal target but down from its all-time high of 133 percent in 2020. The US has an advantage over other countries because it denominates its debt in its own currency through US Treasuries, which are widely considered safe and the government controls its production.

Still, some see this situation as a “runaway freight train” and voiced concern for how long the US will be able to maintain this primacy, anticipating an economic collapse when the music stops and funds available are not sufficient to cover the cost. With debt at this level and interest rates no longer at historic lows, no wealth tax would be sufficient to pay down the debt in a meaningful way. This poses an existential risk for so much of the life to which we have become accustomed in the United States, and looms over all conversations about economic strategy.

Finally, many people commented on how those with resources have become anchored to wealth accumulation and tax avoidance as a primary motivator and marker of success. While this makes sense for people who need to establish financial security for themselves and their families, research shows that money does not bring greater happiness beyond that point.[3] And even those with the most wealth do not always seem to be thriving, with higher wealth not necessarily correlated with greater joy and life satisfaction. Rather than a zero-sum calculation, this raises the question of what the true cost of our current orientation is and whether quality of life might be improved for everyone in a society that prioritized human and planetary health.

I’m curious how this sits with you. Capitalism is so sacred to so many. As a global society, can we wrap our heads around a different way to conceptualize capitalism in service to humanity, or as I get to later in the paper, is it easier to imagine the end of the world than to reimagine capitalism?

[1] Generation Impact: How Next Gen Donors Are Revolutionizing Giving, Sharna Goldseker & Michael Moody, 1/1/2017

[2] Top 1 percent bags over $40 trillion in new wealth during past decade as taxes on the rich reach historic lows, Oxfam International, 7/24/2024

[3] Economic Growth Can’t Buy Happiness, Association for Psychological Science, 10/1/2015

I love this. How lucky to have crossed paths with you (ala Hershey). Looking forward to reading and absorbing your wonderfully gathered concepts!

Interesting piece. The 1980s was pivotal. Carl Icahn and other “greenmail “ proponents broke the relationship between company leaders and workers by threatening shareholder revolts if quarterly earnings and share prices slipped. Short term, shareholder value became the sole determinant of CEO success, another accelerator of the wealth divide and the hollowing out of the middle class.