What’s Climate Got to Do with It?

So now that we have established how the extractive nature of capitalism is a primary driver of our current negative spiral, let’s take a closer look at how changes in climate and the environment are further exacerbating the challenges we face. My goal here is to provide a high-level overview, based on my conversations, but there is so much more to say about the unsustainable way we now live on the planet. ClimateWorks and Climate Lead are both terrific resources for philanthropists looking to do more in climate. 350.org is a great starting point if you want to join the climate movement. And for those looking for accessible climate information, including day-to-day ways to take action, check out Dave Margulius on Climate.

Climate Change and the Environment

If we do not care about the climate crisis and if we do not act now then almost no other question is going to matter in the future… Why should I be studying for a future that soon may not exist?

- Greta Thunberg, World Economic Forum, 2019

Saving our planet, lifting people out of poverty, advancing economic growth... these are one and the same fight. We must connect the dots between climate change, water scarcity, energy shortages, global health, food security and women's empowerment. Solutions to one problem must be solutions for all.

- Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, United Nations General Assembly, September 2011

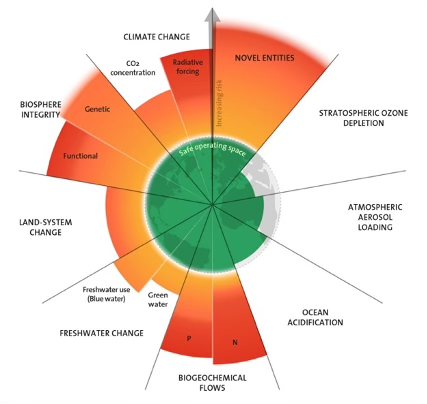

In wrapping my head around the environment and our changing planet, climate scientist Johan Röckstrom’s framework stood out as one that is both comprehensive and clear.[1] While the global conversation tends to focus on climate change, Röckstrom and his colleagues have identified nine processes that regulate stability and resilience of the Earth, and climate is only one. As of 2023, six of the nine have been transgressed. The reality is that the planet is changing – and getting much hotter – much faster than expected, and as each boundary is crossed, it makes it more likely that the others will tip as well.[2]

The result is more extreme weather events causing dramatic personal and economic instability around the globe, from droughts and floods to hurricanes and fires. We are seeing a significant increase in environmental disasters, dislocation, and migration, including the rise of what author Naomi Klein coined “disaster capitalism”[3] where companies capitalize on catastrophes as business opportunities rather than investing in prevention or rebuilding what was lost. Climate anxiety is exacerbated as global media brings these challenges directly into our lives every day, with a profound effect on young people in particular. And the effects of climate change disproportionately impact low-income and marginalized communities who live in the vulnerable frontlines where climate change and planetary degradation hit first, making climate justice a critical lens.

The bottom line is a clear imperative to live within planetary boundaries or risk an end to the stable weather patterns and understood environment that has made it possible for humans to thrive. Efforts to address planetary changes are broadly divided between mitigation, which is primarily scientific, and adaptation, which focuses on communities. On the scientific side, energy takes center stage among investors.[4] In particular, clean energy is making significant strides towards reducing fossil fuel dependency, with renewable sources now making up 30% of global energy use, driven by growth in solar and wind power and a diversification of renewable energy sources.[5] With renewable energy becoming less expensive than fossil fuels starting in 2010 and continuing to become increasingly competitive, the outlook there is quite positive.[6]

Although progress on clean energy is promising and broadly understood, I was fascinated to hear about anticipated scientific breakthroughs that could be even more transformative. Energy is currently expensive and polluting, but between knowledge gained through space exploration and the analytical power of generative AI, some on the private investment side believe free, clean, unlimited energy is possible in the foreseeable future. With unbounded energy, we could actually make all the resources we need, rather than having to work within the constraints of what already exists. As a result, those working in venture capital communicated a gravitas and urgency to their efforts that transcended financial returns and mirrored the mission-driven orientation of those in the nonprofit and philanthropy sectors.

On the flip side, some observed that the cost of energy is the only limitation on our species’ tendency toward rampant consumption, and they fear cheap energy will take the brakes off our insatiable appetite to devour planetary resources. Like so many of the dynamics we balance as a society, this is yet another where we are torn between “capitalism at speed” and the guardrails needed to ensure the progress we make actually benefits people and the planet.

And while some see solutions in science and technology, others find wisdom in returning to indigenous and historical approaches to living on the planet that are grounded in natural cycles. Regenerative agriculture is on the rise, both as a strategy for mitigating climate change and as part of a holistic way to balance human and planetary needs. Industrial agricultural practices have significantly depleted soil quality, with significant carbon sequestration and drought tolerance implications. As a result, current trends of soil loss are threatening global food and climate security. Conversely, if those practices are reversed, agriculture can be a substantial part of the solution, pulling carbon out of the air and improving soil quality. Yet only 3 percent of climate finance is currently allocated to food systems, with greater investment offering the potential for immediate impact.

According to environmental scientist and financial activist David LeZaks Ph.D., regenerative agriculture has myriad benefits but its carbon sequestration potential focuses the conversation too narrowly on climate, positioning agriculture as a silver bullet that could reduce the need for adaptation and ignoring the multifaceted nature of environmental healing. He encourages a broader view that embraces changes in how we eat and manage supply chains, so that the planet can flourish and improve human health, nourishing people into the future.

On the adaptation side, those in the nonprofit sector say climate justice is now part of everything they do, whether they are working in early childhood, K-12 education, vocational training, higher education, housing, racial justice, or any of a myriad of other issues. Given the intertwined nature of these issues, it is inevitable that communities affected by racial inequity and poverty are also the ones whose health and safety is most impacted by climate. They are prioritizing hiring, listening to and partnering with voices of lived experience on those frontlines.

Rather than passively accepting change, local communities are now organizing, pushing back on top-down efforts such as new chemical facilities, companies seeking to extract natural resources, government distributing aid post-disaster, or project-based philanthropy, seeking more control over what is done and how it is done when it comes to their own backyards.

In Florida, where the effects of climate change are currently felt most viscerally, especially with the higher intensity and frequency of hurricanes hitting coastal communities, Governor Ron DeSantis signed a politically-motivated law in May 2024 to restructure the state’s energy policy so that addressing climate change would no longer be a priority. Community leaders Paul Ben-Susan and Julie Ben-Susan say conservative politics and local culture frame the conversation around environmental risk in Florida.

Rather than rising temperatures or carbon emissions, real estate is understood to be the driver of climate degradation due to the development of the flood plain and other coastal buffers to accommodate an influx of outsiders moving to Florida. The impacts are already evident. Releases from Lake Okeechobee into the Gulf turn into the red tide and accompanying blue/green algae, which is harmful to fish and wildlife. The Everglades ecosystem is collapsing and the coastal water near Fort Myers remains highly toxic from cars and bodies that washed out during Hurricane Ian.

Even though these effects cannot all be traced back to real estate, choices developers make are seen as the problem and people moving to Florida as the cause. And if anyone suggests taking steps to address or mitigate climate change, the answer is an echo of the famous Texas refrain: “Don’t California My Florida.”

While growing interest in moving to Florida may be driven more by tax incentives than environmental concerns, climate migration broadly is a significant driver of individual and world instability, with more people on the move as they seek to find stable homes for themselves and their families. The recent drought and famine in northern Africa, which started in 2023 and was exacerbated by food shortages from the Ukraine war, thrust tens of millions of people into acute food insecurity, causing large-scale displacement and leading to significantly increased migration toward Europe.

This dynamic not only affects those families in crisis, but also disrupts the European countries who absorb them, creating a backlash that is still being felt politically with the rise of conservative anti-immigrant candidates and parties. Similarly, the US recently faced unprecedented levels of immigration at the southern border not just from Latin America, but those from Africa, the Middle East, and southeast Asia seeking to find asylum from wars often driven by the changing environment and the drive to secure natural resources such as food and water.

And while progress is certainly being made on climate, it is not enough and the current reality is a warming planet that is rapidly accelerating the pace and intensity of all these phenomena – extreme weather, resource insecurity, migration, job dislocation – and further exacerbating climate anxiety. This accelerating pace of change feeds into the fear created by the growing wealth gap and economic insecurity, which in turn is further exacerbated by the rapid adoption of new technology, especially generative artificial intelligence. In the next post, we’ll look more in-depth at the rise of and implications from generative AI and how it is further compounding the challenges from growing wealth inequality and climate instability.

[1] Planetary Boundaries, Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University, 2023.

[2] Earth beyond six of nine Planetary Boundaries. Richardson, J., Steffen W., Lucht, W., Bendtsen, J., Cornell, S.E., et.al. 2023. Graphic: Azote for Stockholm Resilience Centre, based on analysis in Richardson et al 2023.

[3] The Shock Doctrine, Naomi Klein, 2007

[4] How the World Really Works, Vaclav Smil, 2022

[5] Renewable Energy Progress Tracker, International Energy Agency, 3/29/2025

[6] Graphic: Visualized: Renewable Energy Capacity Through Time (2000-2023), Jennifer West, 6/18/2024